Vineyard worker in the Palacios's vineyards near Corullón take a vino break with a drink from a wine bota.

Vineyard worker in the Palacios's vineyards near Corullón take a vino break with a drink from a wine bota.Share This Gerry Dawes's Spain Post

In 2019, again ranked in the Top 50 Gastronomy Blogs and Websites for Gastronomists & Gastronomes in 2019 by Feedspot. "The Best Gastronomy blogs selected from thousands of Food blogs, Culture blogs and Food Science. We’ve carefully selected these websites because they are actively working to educate, inspire, and empower their readers with . . . high-quality information. (Last Updated Oct 23, 2019)

Over 1,150,000 views since inception, 16,000+ views in January 2020.

36. Gerry Dawes's Spain: An Insider's Guide to Spanish Food, Wine, Culture and Travel gerrydawesspain.com

Photo by John Sconzo, Docsconz: Musings on Food & Life

Custom-designed

Wine, Food, Cultural and Photographic Tours of Spain Organized and Led by Gerry Dawes and Spanish Itinerary Planning

10/17/2007

Mencía: Articles on an Amazing Grape Variety From Northwestern Atlantic Spain

Vineyard worker in the Palacios's vineyards near Corullón take a vino break with a drink from a wine bota.

Vineyard worker in the Palacios's vineyards near Corullón take a vino break with a drink from a wine bota.9/22/2007

New Spain Posts January-September 2007

Some of my faithful readers, among the dozen of you, have expressed concern about the lack of posts and rightfully so. I have been traveling to Spain too much and can't keep up with it all!!! I am now averaging eight trips per year. To cut down on that average, I consolidated what would have been three-four trips in April-May to a one-month stay, so I have done three trips so far this year, a total of nearly eight weeks, and I am overloaded with information and backlogged with photographs. Some times you wish upon star and the star answers.

Posted (click on links below) and upcoming reports include: Read More

9/18/2007

Spain’s Food & Wine Fairs: A Perpetual Feast

All photographs copyright 2008 by Gerry Dawes (Not to be used without permission, gerrydawes@aol.com)

Spanish food and wine fairs, wine trade fairs, , promotional events and gastronomic conferences can keep dedicated Spanish wine professionals, foodies and aficionados alike busy all year round, as I found out over the course of 2007, when I made a half dozen ten trips to Spain, many of them connected two and three deep to Spanish wine events. Spain now has thousands of wineries and it takes a lot of tastings to bring all that wine to the attention of the press, importers and consumers.

In January, it all begins at Madrid Fusión, an annual event, where a roster of the top chefs in Spain—augmented by other star chefs from around the world—come to show the latest superstar cooking techniques. Taking best advantage of the drawing power of the superchefs, ICEX Vinos de España / Wines From Spain puts on a star-studded show of their own at the event. In 2007, celebrating its 25th Anniversary, Wines From Spain presented more than 130 top-rated Spanish wines in several España: Vientos de Terruño / Spain: Winds of Terroir tastings at Madrid Fusión. La Rioja also presented two big panel tastings—one contrasting classic and modern style Rioja reds, the other focusing on versatility of the tempranillo grape.

Tetsuya Wakuda at Madrid Fusión

Tetsuya Wakuda at Madrid Fusión Ferran Adrià with a food producer at Madrid Fusión

Ferran Adrià with a food producer at Madrid Fusión Juli Soler, El Bulli & Teresa Barrenechea, Termomix Spain at Madrid Fusión

Juli Soler, El Bulli & Teresa Barrenechea, Termomix Spain at Madrid Fusión Esmeralda Capel with white truffles

Esmeralda Capel with white truffles José Mari Arzak, Ferran Adrià, Rafael Ansón, Tetsuya Wakuda

José Mari Arzak, Ferran Adrià, Rafael Ansón, Tetsuya Wakuda Wakuda, Trotter, Norman Van Aken and Friends Having Tapas at Rafa in Madrid

Wakuda, Trotter, Norman Van Aken and Friends Having Tapas at Rafa in Madrid

Gerry Dawes and Paul Prudhomme at Madrid Fusión

That was just the beginning. Later that month in Valencia, the sixth edition of Encuentro Verema, one of Spain's most prestigious wine conferences, took place in Valencia on January 26 and 27 at the five-star Meliá Valencia Palace Hotel. The conference, organized by Valencia-based verema.com, one of the world's most visited wine websites, featured two days of high level seminars and tastings. Bodegas Herederos de Marqués de Riscal, presented "The Evolution of Rioja Wines in the Past Century," following by a tasting of historic vintages of Marqués de Riscal Reserva wines back to the stellar, legendary 1945, as well as their 2001 Barón de Chirel, perhaps the greatest in that wine’s history. The next day, Managing Director-Winemaking Team Leader Agustín Santolaya of Bodegas Roda presented a tasting of representative vintages from the winery since its creation. One of the event’s highlights was the presentation of the Verema Awards for 2006 to: Best Bodega 2006: Bodegas Roda; Rising Star Bodega: Viñas del Vero; Best Wine Award 2006: Vega Sicilia Único 1994; Wine Personality of the Year 2006 Award: Mariano García of Bodegas Mauro, Maurodos and other wineries; and Award for Best Restaurant Wine Service: Restaurante Atrio (Cáceres).

León Grau, José Luís Contreras, Verema.com & Ricardo Pérez, Descendientes de J. Palacios, Bierzo

León Grau, José Luís Contreras, Verema.com & Ricardo Pérez, Descendientes de J. Palacios, Bierzo Ricardo Pérez, Descendientes de J. Palacios, Bierzo (left) & Juan Such, Verema.com (right)

Ricardo Pérez, Descendientes de J. Palacios, Bierzo (left) & Juan Such, Verema.com (right) Telmo Rodríguez

Telmo Rodríguez

In early March in Ferrol (A Coruña, Galicia) the Chamber of Commerce of Vilagarcia de Arousa staged the bi-annual (2009 is next) Fevino—Fería de Vino de Noroeste—a show based primarily on the white wines of Galicia, but with exhibitors from around Spain. Here, in a less crowded environment, some 300 bodegas brought more than 1,000 wines to taste. This one is particularly good for importers and the press interested in the wines of northwestern Spain, because sit-down sessions with bodega principals and representatives are available on a one-on-one basis.

Also a bi-annual fair—and the biggest of them all—is the huge Alimentaria fair, a huge event with thousands of exhibitors (which next will take place in Barcelona from March 10-14, 2008). Hundreds of bodegas bring thousands of wines to show and along with a mind-boggling variety of foodstuffs, there is Barcelona’s equivalent of Madrid Fusión, the less well-known, but superb BCNVanguardia Congreso Internacional de Gastronomía de Alimentaria, all of which combine to make Alimentaria a not-to-be-missed event for wine lovers and foodies alike.

Charlie Trotter at BCN Vanguardia

Ferran Àdria at BCN Vanguardia

Juli Soler of El Bulli

In April, back in Madrid at the Casa del Campo, the Grupo Gourmets, for the past 21 years, has staged the Salón Internacional de Gourmets in three different exhibition halls, where some 1,000 exhibitors show an estimated 35,000 products, among them thousands more wines from all around Spain. This is one of best wine and food fairs I know and another no-miss event for wine and food professionals and aficionados of the best of Spanish products. For more than 30 years, Grupo Gourmets has been the publisher of Club de Gourmets magazine and an outstanding guidebook series that includes the annual Gourmetour Guía Gastronómica y Turística de España and the Guía de Vinos Gourmets wine guide.

Three-star Michelin Chefs Santi Santamaria, Ferran Ádria, Paul Bocuse and Juan Mari Arzak at the Salón Internacional de Gourmets in Madrid

Torta del Casar at the Cheese Judging at the Salon Internacional de Gourmets in Madrid

Also in April and coinciding with the Salón de Gourmets, the group behind verema.com, started a new upscale bienial wine event, Vino Elite, which featured some of Spain’s top wineries and seminars by such luminaries as Spanish art film maker José Luís Cuerda (also owner of the D.O. Ribiero wine, Sanclodio), Jonathan Nossiter of Mondovino wine documentary fame and his wife, Paula Pradini, who showed her Mondoespaña segment. The verema.com group and Emiliano García—owner of Casa Montaña (a revered Valencian bodega and tapas bar that dates to 1836) and Aranleón (a very promising new Utiel-Requena winery), also staged another star turn tasting event, Vino a Toda Vela (Wine at Full Sail), one of a string of events celebrating Valencia’s turn at playing host to the America’s Cup yacht races. The event, which featured top wines from Spain and around the world was held in the cloister of the 500-year old monastery that now houses part of the University of Valencia.

Palacio de Congresos, Valencia, site of Vino Elite

Paco Higón, Verema.com; Paula & Jonathan Nossiter

The Feria Nacional del Queso (National Cheese Fair), of Trujillo (Cáceres province) in the region of Extremadura, has taken place the first weekend in May since 1986. Called the most important cheese fair in Europe, this consumer-friendly event has nearly 100 cheesemakers showing some 300 different cheeses, which can be sampled with local wines by buying tickets that are exchanged for tastes at each tented stand. The fair takes place outdoors in Trujillo's spectacular, historic Plaza Mayor, the main square, which is surrounded by distinguished buildings and the large equestrian statue of Francisco Pizarro, the conqueror of Peru.

Cheese Fair in Trujillo's Main Plaza, La Plaza Mayor.

Cheese Fair in Trujillo's Main Plaza, La Plaza Mayor. This is a wonderful fiesta for cheese lovers. All one has to do is show up, make your way to the Plaza on foot, purchase some tickets and enjoy a superb range of artisan cheeses, the majority of which are from Spain and neighboring Portugal. The local Extremaduran cheese such as the ewe's milk Torta de la Serena, Torta del Casar and Tortita de Barros, along with Trujillo's own goats' milk cheese Ibores, are superb and among the best cheeses in Spain.

Cheese stand at Trujillo's Feria del Queso.

Cheese stand at Trujillo's Feria del Queso.Following on the heels of those events was Castilla y León’s most important wine judging event, Premios Zarcillo, in which wineries from this large region’s denominaciones de origen, which includes Ribera del Duero, Rueda, Toro, Bierzo and Cigales, vie for the coveted Zarcillo de Oro top prizes in each category. The judges—a distinguished group of Spanish and international tasters—labors for several days tasting hundreds of wines from the region (and beyond; there are wines from other Spanish wine regions and foreign countries) in an unforgettable setting in the heart of the Ribera del Duero at the 14th-century Castillo de Peñafiel, one of Spain’s most spectacular castles and now the Museum of Wine.

Premios Zarcillo, Peñafiel (Valladolid)

After the Premios Zarcillo, Fenavin (Fería Nacional del Vino), Spain’s biggest annual trade fair dedicated solely to wine, takes place the second week in May in Cuidad Real. Fenavin has more than 1,000 exclusively Spanish bodegas exhibiting in seven pavilions and some 2,500 wine buyers and importers scour the exhibition spaces for four days seeking new treasures for their portfolios. This fair also features some of the best wine seminars in Spain with top experts from the around the world and Spanish experts who are only a short AVE high-speed train ride away from Madrid.

Fenavin, Spain's Largest Wine Fair, Cuidad Real

Another bi-annual fair, and one of the most rewarding, is The Vinoble International Noble Wines Exhibition, is held every two years at the end of May in Jerez de la Frontera. In 2008, it will be staged from May 25 through May 28. It is the only wine fair dedicated exclusively to fortified, dessert, and naturally produced sweet wines, not just from Spain, which has a much overlooked vibrant production of luscious wine in this genre, but from around the world. The setting for Vinoble is Jerez’s beautifully renovated 12th-century Arabic Alcazar fortress, which dates from the Almohade epoch of the Moorish occupation of Spain. The site is spectacular with wine tasting stands occupying the gardens of the Alcazar, and wine tastings such as a Château D'Yquem retrospective and a palo cortado Sherries presentation are held in the complex's former mezquita (mosque) and tasting pavilions in the Renaissance Palace of Villavicencio, which was built within the walls of the fortress in the 17th and 18th centuries. More than 100 noble wine producing areas for from fortified and sweet wines from around the world show their best labels at Vinoble.

Vinoble: Tasting in the former Mezquita of the Alcazar in Jerez de la Frontera

But, at Vinoble, as might be expected, it is the host country, Spain, which shows the most extensive variety of high quality sweet and fortified wines. Local Sherry bodegas bring out a broad range of high quality fortified wines--finos, manzanillas, olorosos, amontillados, creams, pale creams, moscatels and Pedro Ximénez sweet wines, as do bodegas from nearby Andalucian wine regions such as Montilla-Moriles (Cordoba) with a range of finos, amontillados, olorosos and Pedro Ximénez; the Condado de Huelva with fortified Sherry-like wines, including delicious orange essence-flavored ones; and Málaga, which showed some exceptional moscatels. Cataluña was represented by sweet wines from Penedès and Priorat; Valencia by sweet mistela moscatels; Navarra by late harvest moscatels and vinos rancios; Alicante by moscatels and fondillones; Jumilla by late harvest Monastrell-based wines; and Rueda, Rías Baixas and Yecla by late harvest entries.

Only in Jerez at Vinoble can wine professionals and aficionados alike find such a broad range of high quality "Noble" wines. Even one day at Vinoble is an education into this relatively little-known, magical world of late harvest, fortified, botrytisized, dessert and dry wines such as manzanilla, fino and amontillado Sherries. Touring the Spanish stands in May 2006, I was able to taste an amazing array of wines that underscored the importance of this emerging genre of exceptional wines from all around Spain.

All these food and wine fairs take place before June, but there is more. On the first weekend in August, there is the lively Fiesta de Albariño (no permanent website) in Cambados, a charming Galician seaside town in the Val do Salnés region of Spain’s top white wine producing area, Rías Baixas. This region is where a wide range of producers make most of the excellent Albariños that are so food-friendly to modern (and traditional) cuisines have taken American wine lists by storm. Scores of the Val do Salnés region’s best Albariños are available for tasting at open-air stands along an esplanade outside the Parador de Cambados. Top wine journalists (and one American, this writer) taste wines for two days to select the top Albariños each year.

Those who think they might not get enough Albariño at Cambados can show up a week earlier for wonderful, little-known, country Albariño wine fair in Meaño, where more than a dozen small wineries from the Asociación de Bodegueros Artesanos, led by Francisco Dovalo of Cabaleiro do Val, stages a weekend showing of their artisan wines, along with Galician bagpipe music and culinary specialties such as pulpo a la gallega (octopus steamed or grilled and sprinkled with Spanish olive oil, superb Spanish pimentón [paprika] and sea salt) and local shellfish, which is some of the best in the world.

Asociación de Bodegueros Artesanos Emblem

Asociación de Bodegueros Artesanos Emblem With Francisco 'Paco' Dovalo, Presidente of the Asociación de Bodegueros Artesanos at their Albariño wine fair in Meaño.

With Francisco 'Paco' Dovalo, Presidente of the Asociación de Bodegueros Artesanos at their Albariño wine fair in Meaño. I have gone to all the events described in the past two years and was privileged to be invited to speak at several of them. I could have kept on going to any number of Spanish harvest wine fairs in September, October and November, when the great chefs conference, Lo Mejor de la Gastronómía, takes place in San Sebastián, and the excellent IberWine, billed the Salón Internacional de Vino (a biannual event devoted to Spanish and Portuguese wines that alternates between Madrid, Portugal and the U.S.), but even a marathon Spanish wine geek like me needs a respite sometimes. Still, I can’t wait for the next round to start each year.

--The end--

6/06/2007

Toro: The Black Bull of Spain is Poised to Roar into the International Wine Arena

5/27/2007

Press File: English Clips - Spanish Clips

Adrian Murcia's musings on my rant about high alcohol wines from a Spanish wine luncheon at Per Se.

May 17 & May 21, 2007 Two-part Podcast interview at Fenavin by Ryan Opaz, www.catavino.net

Interview with Gerry Dawes, Part One / Part Two

Today, I present part one of an interview I recorded at FENAVIN with Gerry Dawes. Gerry has been traveling Spain for over 30 years and has written several books and articles on his experiences, which have gained both the respect and attention of several other well-known Iberian authors.From beginning to end, the entire interview lasted about 40 minutes and I think its a great peak into Gerry’s career, along with some of his opinions about Spain, Spanish wine and Spanish food. If you’ve been interested in Spain as a culture, you’ve probably read at least one of his articles, if not several over the years without even realizing it. His endless knowledge on the subject is impressive and worth listening to if you desire an understanding of Spain’s gastronomical and wine evolution beginning right after Franco’s three decades of oppression.

I want to thank Gerry for taking the time to talk with me, and I look forward to crossing paths with him many more times as we continue to explore Iberia.

Cheers, Ryan Opaz

5/26/2007

Gerry Dawes's New Spain Web Log

Writing, Photography, Speaking Engagements, Culinary & Wine Trips to Spain, Spanish Travel Planning

Available for writing assignments, photography assignments (digital and transparencies), and speaking engagements on Spanish gastronomy, wine, cheeses, travel, etc.

Recent Appearances (Autumn, 2006)

I also customize and lead culinary and wine tours to Spain and do Spanish travel planning.

Contact: gerrydawes@aol.com

"Gerry Dawes--has emerged as the leading American speaker, consultant, and writer on the subject of Spanish wine. . . suffice to say that everyone from The New York Times to the James Beard Foundation, from 60 Minutes to CNN, has sought Gerry's wisdom on... Spanish wine, food and culture." - David Rosengarten, The Rosengarten Report

(Note: To see photographs at optimum quality, please double click on each picture.)

Premio Nacional de Gastronomía 2003 (Spanish National Gastronomy Prize): 2003 Marques de Busianos Award from the Academia Española de Gastronomía (Spanish Academy of Gastronomy) & La Cofradia de la Buena Mesa for writing, photography, and lectures about Spanish gastronomy and wines. At the Casino de Madrid, with Lourdes Plana of Madrid Fusion & Teresa Barrenechea, Chef-owner of Marichu (New York)

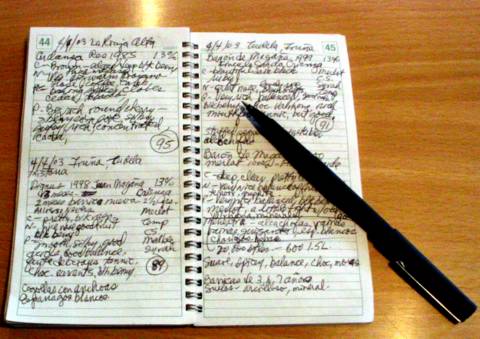

Gerry Dawes has been traveling in Spain for more than three decades. Since 1995, he has made sixty extensive food and wine trips to Spain, twenty since 2003 alone. In his Daytimer notebooks, he has written down every dish and every wine he has had in Spain for the past 15 years and photographs most of the dishes with digital cameras.

Gerry's notebook - Navarra, April 2003

Gerry Dawes copyright 2004

Only non-Spaniard to receive the prestigious Premio Cena de Los 11 Vinos, an award created to honor those who have made significant lifetime contribution to enhancing the image and culture of Spanish wines (for writing on Spanish wines.)

Marqués de Vargas & wife Anya, Gabriela Llamas, Gerry Dawes at Casino de Madrid, Cava Writing Award Presentation, May 2004. Primer Premio--Artículo sobre Cava, Instituto de Cava (Barcelona, Spain): First Prize of 12,000 Euros for Bebiendo Estrellas (Drinking Stars), an article on Spanish Cava (Spanish sparkling wine), written in Spanish for Cocina Futuro magazine (Madrid).

Click for Gerry Dawes Biography & Credits

Gerry Dawes

17 Charnwood Drive - Suite A

Montebello, NY 10901

Cell phone: 914-414-6982

Phone & Fax (call before faxing): 845-368-3486

Telefono movil (durante estancias en España): (011 34) 670 67 39 34

Contact: gerrydawes@aol.com

5/07/2007

New Spain Posts January-September 2007

Posted (click on links below) and upcoming reports include:

In January, Madrid Fusión and Valencia's Encuentro Verema

In March, more Madrid, a wild, exhilarating swing through all the D.O.s of Galicia (Valdeorras, Rías Baixas, Ribeira Sacra, Ribeiro and Monterrei) in early March and a return to Arévalo for supernal roast suckling pig at Las Cubas.

And in April-May, Madrid again (after all, I am an official "Amigo de Madrid") for Grupo Gourmet's annual Salón Internaciónal de Gourmets

Valencia (Vino Elite & Vino a Toda Vela) with reports on paellas (arroces & fideua), the surprising gastonomic scene in Valencia and Alicante and encounters of another kind with Jonathan Nossiter of Mondovino fame and his wife, Paula Pradini, who showed her MondoEspaña film at Vino Elite.

Another visit to wonderful, under-rated Chinchón

Trujillo's exceptional Feria de Quesos in Extremadura

A visit to an old friend at Restaurante Cala Fornells in Salamanca

Castilla y León's prestigious Premios Zarcillo at which prizes are awarded to the best wines submitted (from around the world), the vast majority of which are from the Castilla y León region, which includes Ribera del Duero, Rueda, Toro, Cigales & Bierzo and Vinos de la Tierra de Castilla y León)

Valladolid, getting re-acquainted with Castilla y León's historic, but modern capital city

Cuídad Real for the Fenavin (Feria Naciónal del Vino; Spain's biggest wine fair) and a re-visit to Mesón del Corregidor in Almagro

And, remarkable Toledo, where chef-restaurateur-bodeguero Adolfo Muñoz and his family (Julita, his wife, and Adolfo and Javier, his sons) took me and my traveling companion captive for nearly 24 hours and charged a handsome ransom. We had to visit their Viñedos Cigarral de Santa María property, which has drop-dead views overlooking Toledo (a stone's throw away) and has a 300+ seat restaurant for weddings and banquets. The cigarral is surrounded by their Pago del Ama vineyards, olive groves and gardens with aromatic plants and flowers that play an important role in Adolfo (and his chef son Adolfo's cooking. We were sequestered for the night in the five-star Hotel Palacio de Eugenia de Montijo hotel where Adolfo operates Belvis restaurant, had dinner at Aldofo restaurant (considered the best in Toledo) and, with Adolfo and restaurant director-summiller son, Javier, we got a private tour of their extensive wine collection, which is housed in the cellars of a 9th-century Jewish home in the old quarter. The next morning we had a tapas-"breakfast" at Adolfo Colección restaurant-delicatessen, then, after re-acquainting myself with monumental Toledo and re-visiting the Santa María La Blanca and Tránsito syngogues (a first for my friend), plus a damascene ware shop, it was back for a farewell lunch at Restaurante Adolfo in Toledo's old Jewish quarter.

After lunch at Adolfo, we headed for Madrid for another remarkable seafood dinner at Casa Mundi, one of a series of remarkable meals with my new-found friend, José Luís Cuerda, the great Spanish film director, producer and screen writer (Bosque Animado, La Lengua de Las Mariposas, Amanecer, The Others and more). Cuerda also owns vineyards and a winery, Sanclodio, in Galicia's Ribeiro, where he produces a delicious treixadura-based white wine, which will soon be available on the East Coast and is the subject of a New York Times article due to be published in late June (for more info on Sanclodio, e-mail alex@marblehillcellars ).

I am going back to Spain in June for two weeks and I will have reports on trout fishing in La Rioja and a much anticipated dinner at Bodegas Riojanas in Cenicero, the wedding of my friend, chef-cookbook author (The Cuisines of Spain, The Basque Table) Teresa Barrenechea's daughter, Maria, in Madrid; the Grupo Gourmet Gourmet Plus Gastronomic Feria in Bilbao at the Palacio Eskalduna from June 15-17; the superb rosados, moscatels and red wines from Navarra; plans for Expo 2008 in Zaragoza; the lastest developments in Cava, Conca de Barberá, & Priorat; another dinner at unbeatable Ca Sento in Valencia; another adventure in Alicante with my friend, María José San Román and her husband, "El Portero Pitu," owners of Monastrell, la Taberna del Gourmet and other excellent restaurants;" and a dash via Jumilla back to Madrid for yet another dinner with Sr. Cuerda, with whom I am planning a Spanish television series based on many of the adventures, people, places, wines and food you are reading about here.

After Spain, it is off to speak at several wine and Spanish artisanal cheese seminars at the Telluride Wine Festival (June 28-July 1), stopping off in Dolores, Colorado, 60 miles south of Telluride, to see my daughter Erica, her husband Ivan and my adorable Gerber Baby grandson, Graham Robert. I keep telling this now eight-month old wonder that I am his Tio Geraldo!

In July, I will be in Portugal's cork country with the Amorim cork producers to report on the state of wine corks. Despite the problems with so-called "cork taint"--many instances of which are not the fault of a cork at all--is an issue that is being successfully addressed by cork producers, for me and many other long-time wine world observers (and participants!!) abandoning the cork for plastic "corks," synthetic closures and the God Awful screw cap is not the answer (scientifically, aesthetically, romantically, image-wise and otherwise).

From Portugal, I will migrate via Oporto back into Spain and spend more time in Galicia, where within a few years fascinating, terroir-driven, indigenous varietal wines will put Spanish white wines on a par with those of the Loire Valley in France (the godello grape has the potential to rival some chardonnays from Burgundy!).

Projecting to September, I will be traveling in Murcia for an in-depth re-visit to the land of the Monastrell grape, Jumilla, Yecla and Bullas.

And, for November, see A Taste of Spain Tour of La Mancha and Andalucía for my cultural, gastronomic and wine tour.

5/04/2007

Valencia: Damned Near Everything You Need to Know About the Incredible Food, Wine & Cultural Scene in Valencia & Alicante

The Surprising Cuisines of La Comunitat Valenciana (Valencia, Alicante & Castellón)

Alicante: Monastrell & La Taberna del Gourmet

The Wines of La Comunitat Valenciana--Valencia, Alicante, Utiel-Requena: Hitting Their Stride as Their Home Region Hosts the America’s Cup

4/21/2007

The Wines of La Comunitat Valenciana--Valencia, Alicante, Utiel-Requena: Hitting Their Stride as Their Home Region Hosts the America’s Cup

But in recent years, a new dynamic has emerged. Mega Euros have poured into Valencia and the surrounding region fueling an unprecedented building boom. Valencia recently completed the multi-billion dollar La Cuitat des Arts y Ciencies (City of Arts and Sciences), Europe's largest and most advanced such cultural-leisure complex (see), and will play host in 2007 to the world’s most prestigious yacht race, the 32cd America's Cup (see box). This coming of age for one of Spain’s most historically rich regions has spawned a cultural renaissance (the riverbed of the diverted Río Turia is home to La Cuitat des Arts y Ciencies and is now dubbed the Río CulTuria); a growing awareness that Valencian cuisine is among the country’s most distinguished; and that a new wave of wines from Valencia’s three denominaciones de origen (D.O.s)–Alicante, Utiel-Requena and Valencia–are emerging as serious quality contenders. (The importance of wine here is underscored by Verema.com, a locally based wine website with a global following that sponsors a high quality wine conference in Valencia every year).

The influx of money coming into the Comunitat Valenciana has also provided the essential platform to support an important modern cuisine movement–led by Paco Torreblanca, one of the world's greatest pastry chefs, and two of Spain's top young cocina de vanguardia stars, Raúl Aleixandre and Quique Dacosta, as well as some of the most rewarding traditional cuisine restaurants in Spain all of which have drawn attention to Valencian wines in their wake.

Heretofore, only dedicated wine aficionados were aware that this warm Mediterranean region–whose inland higher elevation vineyards are rarely seen by those flocking to the popular beaches of the Costa Blanca–encompasses one of Spain’s largest vineyard areas. La Comunitat Valenciana is located along Spain’s south central coast between Cataluña and Murcia. The vineyards of this region grow on land that rises rapidly inland from the coast to significant elevations. Until recently, the region’s wines had a poor reputation, except those aforementioned moscatel romano-based sweet white wines from Alicante and Valencia and Fondillón, a classic, monastrell-based vino rancio (a purposely oxidized, slightly sweet wine), a once nearly extinct wine.

To understand why the Valencian community is emerging as an area with aspirations to produce quality wines requires some historical context. As recently as twenty years ago, the only wines most wine drinkers outside Spain knew were sherries, table wines from La Rioja, Penedès, and the legendary Vega Sicilia. And, until the turn of this century, most of the wines from the three Valenciana D.O.s were rustic, powerful high volume wines produced for blending or for low-end chain store sales in northern Europe. But, in the late 1980s and 1990s, wine regions such as the Ribera del Duero, Navarra, Priorat, Rueda, Toro, Rías Baíxas Albariño, and single vineyard wines from La Rioja all emerged as worthy of serious consideration by international wine connoisseurs.

On the heels of those successes and in an epoch with a growing international acceptance of dark, ripe rich, higher-octane, new oak-aged wines, producers in the warm country areas of Spain, especially in La Mancha and the Levante (Valencia and Murcia), saw a promising opportunity. In recent years, it has become obvious that with proper vineyard and water management, modern production facilities, and savvy winemakers, a wine fitting the modern international profile can be made just about any place in Spain’s warmer areas. Since Spain has more land planted in vineyards than any other country, if the warm country areas such Australia, South America, South Africa and, indeed, California’s Napa Valley, could produce wines that drew positive, sometimes rave international reviews, why couldn’t similar wines aimed at the new world wine order palate be made in areas such as the Comunitat Valenciana?

On several trips (five in total) since 2003 to La Comunitat Valenciana’s seldom-visited D.O.s, I found a region undergoing dynamic change that happily included quantum leaps in quality in the passage of just three years. Most wineries are now fully modernized and, though many are producing large quantities of wine that is technically correct, if still not totally out of the vino corriente category, several others, while still working their way through the winemaking and viticultural learning curve, are producing reasonably priced good, if not great, wines. I also encountered a number seriously noteworthy producers of both table and dessert wines and a few youth-driven new wineries deserving serious attention.

Established Valencian producers have been rapidly upgrading their winemaking facilities and technology as successful professionals and entrepreneurs, like those in Napa and Sonoma in earlier decades, are building new wineries. Many producers draw on high quality fruit from unirrigated old vines vineyards, many others have planted new vineyards, often with the foreign varieties such as cabernet sauvignon, merlot and syrah trained on wires and equipped with drip irrigation systems. Successful producers from other parts of Spain, such as Juan Carlos López de la Calle, producer of La Rioja’s powerhouse Artadi wines (Grandes Añadas, El Pisón); Galicia’s Agro de Bazán (Gran Bazán Rías Baixas Albariño); and peripatetic winemaker Telmo Rodríguez, originally from Rioja’s Remelluri estate; are now making red wines in Utiel-Requena and Alicante. Consulting enologists such Sara Pérez of Priorat’s Clos Martinet coached fledgling wineries such as Valencia’s promising Celler de Roure. American importers including Stephen Metzler of Classical Wines (Seattle), who recognized the quality of Alicante’s dessert wines early on and begin representing Felipe Gútierrez de la Vega’s Casta Diva some two decades ago, and others like Eric Solomon of European Cellars realized that the region’s concentrated wines are no more powerful than average Napa Valley reds, have made serious commitments in the region.

Historically, the best wines of the Valencian region were semi-sweet to sweet vinos rancios (wines made purposely in oxidative environment) and mistelas (fresh grape must whose fermentation is cut short by the addition of alcohol). Such wines have been made here for centuries—probably since before the epoch of the Moors, among whom there were plenty of Koran-defying imbibers (Spanish Arabic poetry celebrated the virtues of wine and other beverages containing al-quol, an import from the Islamic world). Table wines were another story, however. Valencia and Utiel-Requena, especially, were known producing large quantities of marginal rustic whites and rosé wines for export to northern Europe, but, primarily the region was a major source of bulk wines, much of which were vinos de doble pasta.

Michel Grin, Managing Director of Bodegas Murviedro, who makes wines (95% of which is exported) in Utiel-Requena, Alicante and Valencia D.O.s, says “Vinos de doble pasta are wines made by taking the pasta, or mass of grapeskins, pulp and pips leftover from brief contact with the musts used to make rosés and adding it to the cap already fermenting with red wines, thus doubling up on mass of grapes in a vat. This produces a well-colored, neutral-tasting bulk wine that is ideal for blending with other wines to be sold especially in Nordic markets.”

These bulk wines were shipped from huge warehouses located in Valencia’s historic Grao port area–now completing a major America’s cup makeover to play host to the America’s Cup that includes a marina with more than 600 new berths. But, now most of these shippers have moved out to the hilly Valencia and Utiel-Requena wine-growing areas and made serious investments in new bodegas (winemaking and storage facilities) and vineyards. Among them are Michel Grin’s 1,000,000 case Bodegas Murviedro (formerly known as Schenk) and Vicente Gandía Plá’s Hoya de Cadenas spectacular, new 400,000-plus case bodega in Cuevas de Utiel (Valencia). Andres Proensa, one of Spain’s top wine writers, noted a market-driven change in the basic philosophy of Valencia’s large wine shippers. “They have undergone an important transformation by moving their operations from the port out to the wine country,” Proensa wrote.”

The major thrust of the large producers in the Valencia and Utiel-Requena D.O.s is the production of red wines, including 100% varietal red wines and blends of the native Valencian red varieties monastrell (mourvedre), bobal, and garnacha (usually old vines); Spain’s most important red wine variety, tempranillo; and the foreign grapes cabernet sauvignon, merlot, and, very promising for this warm region, high quality syrah, the great grape of France’s Rhone Valley. They are also producing fresher, cold-fermented white wines from the traditional meserguera, macabeo (viura) and moscatel romano varieties and some chardonnays, albeit not yet distinguished ones. Worth seeking out are the fresh, bright, quaffable rosados, based on the little-known local bobal grape, produced by several Utiel-Requena bodegas.

Bobal, which is the main grape of Utiel-Requena was so little known outside Spain, that as late as 2004, Frank J. Prial wrote in The New York Times in an article on Spanish rosados, “Until someone mentioned it to me recently, I had never heard of it. Bobal is something of a mutt grape. No wine made from it can qualify for Spain's strict denominación de origen rating, which specifies grape varieties and methods of production and exercises other quality controls. So it is unlikely ever to leave Spain. Not legitimately, anyway.”

As it turns out, Bobal is one of only three indigenous red varieties (bobal, tempranillo and garnacha) authorized by the Utiel-Requeña denominación de origen, which is located in Valencia province some 45 miles west of the capital and centered around the long-time wine towns of Utiel and Requena. Utiel-Requeña’s some 75,000 acres of vineyards, which range in altitude from 1,900 to 2,000 feet above sea level, are planted with 80% bobal. In 2001, 60% of Utiel-Requena’s production (more than 4,200,000 gallons) was exported, so wines made from bobal have been leaving Spain “legitimately” in large quantities. The hefty bobal, apart from being used in Utiel-Requeña to make some of Spain’s best and most interesting rosados, is being used by Mustiguillo, one of the new wave heroes from the region, as the basis of several wines that have drawn high praise from reviewers, both in Spain and abroad.

Mustiguillo, a charming small winery built on the site of a former stable, has become the star of the Utiel-Requena, despite the fact that they sell their wines with non-denominación de origen status. Mustiguillo’s owner, Toni Sarrión, a contractor who builds public works projects, is, as Andrés Proensa points out “of short winemaking tradition,” but he has become a new wave Comunitat Valenciana hero alongside Pablo Calatayud of Valencia’s Celler de Roure and Pepe Mendoza from Alicante’s Bodegas Enrique Mendoza. From their own vines, Mustiguillo makes two small production, high-end wines, Finca Terrazo—a blend of 40 % old vines bobal (planted in 1912), 40% tempranillo and 20% cabernet sauvignon—and Quincha Corral—76% old vines bobal, 20% tempranillo and 4% cabernet sauvignon. These massive, inky, intensely rich, unfined/unfiltered reds tip the scales at 14.5% alcohol. Finca Terrazo is fermented in 3,500- and 5,000-liter Radoux tinajas (wooden upright vats) and spends up to 16 months in 70% French oak and 30% American, all of it either new or second year. Quincha Corral 2000, a wine with a 500-case per year production and a hefty price, also spends 16 months oak, 100% French oak, mostly new. On the palate it shows very rich, sweet, Port-like, ripe black cherry and cassis fruit and baker’s chocolate with a noticeable ration of new oak. Mustiguillo Mestizaje, also labelled vino de al tierra (non DO), comes mostly from young tempranillo, cabernet sauvignon, and syrah grapes blended with some older vines bobal and garnacha. of big highly extracted black fruits, new oak-lashed house style. Mustiguillo eventually plans to produce 10,000 cases of wine.

At their impressive Hoya de Cadenas estate near Cuevas de Utiel, well-regarded Bodegas Gandía (Vicente Gandía Plá, founded in 1885), is making its mark with Hoya de Cadenas Reserva Privada (85% tempranillo/15% cabernet sauvignon) and Ceremonia, (also a tempranillo/cabernet sauvignon blend), whose new oak is balanced with a nice melange of rich blackberry, chocolate and licorice flavors. This bodega gives some nodding consideration in its top-of-the line Vicente Gandía ‘Generación I’ to the native Utiel-Requena grape by using 50% bobal blended with cabernet sauvignon, tempranillo and garnacha, but the focus here is on nearly 450 acres of wire-trained plantings of tempranillo and cabernet sauvignon, along with chardonnay and sauvignon blanc (they market a palatable 35% sauvignon blanc/65% chardonnay blend).

Bodegas Murviedro (formerly Bodegas Schenk), partially Swiss owned, may be a huge winery with New World styled wine ambitions, but it produces some good, serviceable wines including the Las Lomas de Requena 100% bobal rosado and a carbonic maceration bobal tinto joven.. Murviedro’s premium wines include a well-balanced Coronilla bobal crianza with black cherry and cassis flavors and a stylish Coronilla Reserva blend of bobal, cabernet sauvignon and merlot.

Mas de Bazán, owned by the producer of Gran Bazán from Rías Baixas, is another important Utiel-Requena project. The winery, whose epoxy-lined cement fermentation and storage vats are decorated with early 20th-century Valencian ceramics tiles, is unusual and exceptionally attractive. The vineyards carry the stamp of hundreds of other new Spanish winemaking operations with predominately new plantings are trained on wires outfitted with drip Like most new wineries, the flavors of roble nuevo (new oak)–Allier and some American– dominates the red wines, generally blends of bobal (45%), tempranillo (45%) and cabernet sauvignon (10%). Mas de Bazán also makes a refreshing dry bobal rosado with flavors that bring strawberries to mind.

Bodegas Iranzo’s Finca Cañada Honda property has been a wine-growing estate since the 14th Century. The Pérez Duque family says they have been making wines since 1896, but their ownership of the Iranzo property dates to 1940 and the plantation of the non-Valencian varieties, tempranillo, cabernet sauvignon and merlot (they also have Bobal and Graciano), dates to 1984. Among their wines, billed as vinos écologicos (from organically farmed vineyards), are the Finca Cañada Honda tempranillo-cabernet sauvignon based, tinto joven, tinto roble and crianza; the smooth, ripe, tempranillo-based Mi Niña; the round, plummy, spicy Vertus tempranillo crianza; and Bodegas Iranzo Tempranillo Selección.

An exceptionally promising new Utiel-Requena winery, Dominio de Aranleón, is owned by Emiliano García, who is also the proprietor of Casa Montaña (in Valencia’s El Cabanyal district, an urban “bodega” that dates to 1836 and is one of the best wine and tapas bars in the capital. García also owns Casa Montaña wine shop and tasting salon, located across the street. He makes two very high quality, delicious Aranleón 50% tempranillo, 50% cabernet sauvignon blends with an ingenious snail design that spells out the bodega’s creed on the label.

Another of the best wines I tasted from this region is made by a German winemaker, Heiner Sauer from the Pfalz, at Bodegas Palmera and does carry the Utiel-Requena DO. The very ripe, powerful (14.5%), but silky and exotic, cassis-flavored L’Angelet d’Or, tasted over luncheon at the Aleixandre family’s superb Ca Sento restaurant in Valencia, was one of the best wines I tasted in two trips. The luncheon that L’Angelet d’Or accompanied was one of my most memorable and gratifying meals in Spain.

Viñedos y Bodegas Vegalfaro makes one of the better Syrah/Shiraz wines in the region, Pago de los Balagueses, a deep black, rich, delicious, wine laced with dark chocolate; Bodegas Los Marchos Miguelius Tinto Crianza, a rich, very ripe, exotic, is one of the best expressions of the bobal grape in the region; and Vicente García’s Pago de Tharsys outside Requena is making some of the most interesting and palatable wines in the area, including a good Vendemia Nocturna white wine (made from godello and albariño), a very good ‘Selección Bodega’ made with 95% merlot and 5% cabernet franc; and an 80% merlot, 20% cabernet franc (all non-D.O. wines due to the grapes used), and the Utiel-Requena D.O. Carlota Suria, a cabernet sauvignon-tempranillo blend. Pago de Tharsys also makes an excellent Cava from macabeo and chardonnay grapes, then as a label dangles a distinctive, artistic piece of Valencian ceramics from a ribbon attached to the bottle’s neck. (Pago de Tharsys is not the only Comunitat Valenciana winery producing cava. Dominio de la Vega, who is also making some interesting white wines based on macabeo (viura) and chardonnay, plus a very good bobal rosado, also produces some very good reserva especial vintage, vintage brut nature and brut rosado cavas, the last from 100% garnacha grapes. Torre Orio is perhaps the largest producer of Cava in the region with seven different budget priced cuvees.

Chozas Carrascal, which, unusual for this region, produces a barrel fermented chardonnay, macabeo (viura) and sauvignon blanc blend called Las Tres, a Las Cuatro rosado (tempranillo, garnacha, merlot, syrah), the very unique Las Ocho (a blend of eight red grapes, including cabernet franc), a Family Cabernet and a Family Garnacha under the guidance of French enologist, Michel Poudou. Other wineries of note include Casa del Pinar, which produces two good five-red grape blends (bobal, tempranillo, cabernet sauvignon, merlot and syrah), Sanfir crianza and Casa del Pinar Reserva; Finca San Blas, which produces Labor del Almadeque, well-crafted wines that are members of the tempranillo-cabernet sauvignon-merlot-syrah brigade; and Vera de Estenas, which makes barrel fermented Chardonnay and Merlot, a crianza and a reserva. while Bodegas Sebirán, producers of the Coto d’Arcis line, though they sometimes use 15% cabernet sauvignon, rely more on the indigenous varieties including the once-maligned bobal.

Utiel-Requena wines showing promise at a tasting luncheon arranged by the DOs consejo regulador (regulatory council) were several bobal-based (sometimes blended with garnacha) rosados, Bodegas Torroja Cañada Mazán and Valle de Tejo; a fruity, intense, oak-aged Dominio de la Vega, a red blend of bobal, cabernet sauvignon and tempranillo; a surprisingly well-balanced, barrel-fermented Bodegas Torroja Sybarus Bobal Edición Limitada (1250 cases made from 30-year old bobal); and the organically produced Dominio de Arenal Syrah.

Alicante

Grape vines were introduced into Alicante by the Phoenicians, wine was made here by the Romans and the praises of Alicante wines were even sung by the Moors. The Alicante D.O. encompasses 37,000 acres divided into two sub-regions in Alicante province: the Alicante subzone (northwest of the capital, Alicante), whose main growing area is the Vinalopó river valley, and La Marina, just inland from the area’s popular beach towns. The winters are short and the nearly rainless summers are long and hot.

Producers of the widely renowned Casta Diva moscatels, Bodegas Gutiérrez de la Vega, has shown that Alicante can make world-class dessert wines. An affable, well-read Renaissance man who dresses in a blue lab coat and plays opera (the superb Valencian-born, Caruso-contemporary tenor Antonio Cortis and Montserrat Caballé) as he works in his pristine winery in Parcent, Felipe Gútierrez de la Vega, is the owner-winemaker. Made from moscatel de Alejandria (also called moscatel romano) grapes grown in the coastal La Marina subzone, Gútierrez’s Casta Diva Cosecha Miel is a luscious dessert wine that is a great match to such dishes as star Alicante chef Quique Dacosta’s laminas de foie gras (layered foie gras with a fragrant apple compote) at the superb El Poblet in nearby Denia. Gútierrez also produces several other excellent wines including a dry white moscatel romano, a good bobal rosado, and several interesting reds, including Imagine (dedicated to John Lennon), Viña Ulises (James Joyce and Homer), and Rojo y Negro (Nobel prize winner Camilo José Cela), plus a silky, exotic blend of giró (a garnacha relative), monastrell, cabernet sauvignon, tempranillo, and merlot that spends 18 months in oak, only 20% of which is new (a practice one wishes more winemakers would adopt).

Pepe Mendoza, the winemaker at Bodegas Enrique Mendoza, an aficionado of New World wines. Regarded by new-wave aficionados within Spain as the great revelation of Alicante, Mendoza has received rave reviews from Spanish wine writers for his barrel-fermented chardonnays; full-bodied, ripe cabernet sauvignons; his notable Shiraz, now a big attention getter in Spain; a Pinot Noir with real potential; his famous Santa Rosa Reserva 1998 (a powerful, rich, oaky blend of cabernet sauvignon, syrah, and merlot); and the Selección Peñon de Ifach, a good, if unorthodox, blend of cabernet sauvignon, merlot and pinot noir.

Laderas de Pinoso (producers of El Sequé) is an Alicante winery with a built-in immediate appeal. It was founded in 1999 by Juan Carlos López de la Calle of La Rioja’s Bodegas Artadi fame and Agapito Rico, producer of Carchelo, a delicious monastrell-based Jumilla red. The Bordeaux-esque Laderas de El Sequé, a monastrell, tempranillo, cabernet sauvignon and syrah blend that spends fewer than six months in oak; El Sequé, a similar blend (with 50% tempranillo), which is a well-made, richer wine, whose finish is dominated by new oak.. The bodega is located in Pinoso (Alicante), a town famous in Spain for its arroz de conejo y caracoles (rabbit-and-snail paella) at Casa Paco, a restaurant legendary for this dish, and Restaurante Casa Elias, in the nearby village of Xinorlet, which is a lesser-known, but exceptional restaurant choice.

At Casa Elias, accompanied by an excellent plate of assorted cured artisanal sausages, wonderful grilled wild mushrooms and a superb rabbit-and-snail thin-layered arroz en paella cooked over grape vine cuttings and served with authentic all-i-oli, I tasted a lineup of wines with Rafael Poveda from Salvador Poveda, a the family bodega that produces Alicante’s most renowned Fondillón (see below). Poveda’s intense red table wines included a good Poveda Tempranillo; a big, complex, cherry-and carob flavored Borrasca Classic Tinto from their Finca El Pou estate’s 50-year old monastrell vines; and the massive, oak-dominated, 100% monastrell, Borrasco Tinto Selección de Barrica (only 600 bottles made).

Almuvedre, a powerful 100% monastrell tinto joven (young red) made by Telmo Rodríguez, the peripetatic, “flying winemaker,” who began at his family’s Remelluri estate in La Rioja and now makes Compañía de Vinos Telmo Rodríguez wines in the Ribera del Duero, Toro, Málaga and other regions, is another notable Alicante table wine that has recently emerged in recent years.

Forward-looking Bocopa is one of the top wine cooperatives in Spain. Known for its first-rate Fondillón Alone (see below), Bocopa also makes the fresh, delicious, off-dry white wine Marina Alta Blanco Gran Selección moscatel; Laudum, a soft, rich monastrell-based, American oak aged crianza red; and Marqués de Alicante, a palate-pleasing crianza blend of monastrell, tempranillo, cabernet sauvignon, and merlot. Bocopa also makes two spectacular vinos de licor–wines typical of this region in which the fermentation of grape must (mistela) is arrested by the addition of orujo, or grape spirits, resulting in lusciously sweet, fresh tasting dessert wines. Marina Alta is an intense sweet white wine with honeysuckle flavors and the dark, delicious Sol de Alicante Dulce Negra (100% monastrell) tastes of black fruit compote, raisins, and chocolate-laced coffee liqueur.

Three other Alicante wineries drawing attention recently are Bodegas Sanbert, which makes a smooth easy drinking monastrell Camps de Gloria Rodriguillo reserva; Bodegas Bernabé Navarro, whose Beryna is made by Joaquin Galvez, who has worked at California’s famed Ridge Vineyards; and Vins de Comtat, whose non-D.O. Penya Cadiella red from the L’Alcudia-Concentina area, uses five different varieties–including monastrell, merlot, giró, tempranillo and cabernet sauvignon–to achieve a smooth balanced wine with wild berry, plum and dark chocolate flavors.

Valle del Carche, in Alicante province, is a promising 400-acre estate with a preponderance of monastrell vineyards. Situated only eight miles from the town of Jumilla in neighboring Murcia, Valle del Carche, also qualifies to produce Jumilla wines, as well as . Alicante D.O. wines, which are made of either cabernet sauvignon, merlot, syrah, tempranillo or blends of those grapes. The most of impressive Valle del Carche’s wines were the easy-drinking Porta Regia Syrah (tasting of currants and baker’s chocolate) and the dark, smooth Domus Romans Reserva 1998 tempranillo/cabernet sauvignon, merlot blend aged in American oak barrels with French oak ends. These wines went very well with an excellent paella cooked over a wood fire by Tomasa, Valle del Carche’s fine country cook.

Alicante’s classic Fondillón, a red grape-based noble wine and a favorite of France’s Louis XIV (the Sun King) and of Alexandre Dumas pere’s fictional Count of Monte Cristo, is a revelation. A wine with 500 years of written history (supposedly Fondillón was on Magellan’s ill-fated trip around the world), until recently, this semi-sweet, monastrell-based rancio wine, aged for a minimum of eight years and usually more than twenty before being released, was nearly extinct except for a few wines made by small family bodegas.

The centenarian Salvador Poveda bodega in Monóvar is the top producer of Fondillón and largely responsible for the recuperation of this legendary Alicante classic that until recently was all but forgotten. The star of Poveda’s stable is their Salvador Poveda Gran Reserva de Fondillón 1980, a splendid, profound, mahogany-colored jewel that tastes literally like someone mixed a great oloroso sherry with a vintage ports and can justifiably be called one of Spain’s greatest “noble” wines, a category that includes all of Andalucía’s superb Sherries.

Rafael Poveda explains how his fondillón is made: “We use 100% Vinalopó valley monastrell grapes selected during the best harvests. They have a very high concentration of sugar–always higher than 16°Baumé, often 18°. We sometimes put the grapes out on mats in the sun for several days to increase the sugar concentration. The must is left in contact with the skins only until it begins to ferment, so skin contact is very short, therefore the wine is born as soft, fruity and light-colored as a Bordeaux, but without the tannic astringency. When the fermentation is finished, we have a very aromatic, medium-dry wine that we age in old oak barrels, usually in a sherry-like solera. But, in an exceptional vintage like 1980, we age the wine separately without mixing it in the solera to make an authentic vintage Fondillón.”

Felipe Gútierrez de la Vega also makes the excellent Casta Diva Fondillón (dedicated to William Blake). Unlike the Povedas, who do short macerations, Gútierrez macerates his 100% monastrell grapes for 20-30 days. He says the wine can ferment up to two months, which leaves it at 17-18 percent natural alcohol. Made from grapes that are allowed to hang on the vine until they become raisiny–unlike the grapes for many other Fondillóns and sherry Pedro Ximénez grapes, which are picked and sun-dried on mats. After Gútierrezages it for 15 years, the result is a Fondillón that is deep plummy, spicy, very rich and Port-like, but is unfortified, thus natural.

Another good fondillón, Bodegas Bocopa’s Alone (ah-lo-nay), is also a well-made, solera-aged, red monastrell-based dessert wine. Some of these fondillóns are reminiscent of tawny Port, others such as Bodegas Brotons Gran Fondillón Reserva 1964, Primitivo Quilés Fondillón (Hístorico) ‘El Abuelo’ Gran Reserva and Poveda Añejo Seco (made from Vidueño, an old Monastrell clone), are very much like great palo cortado Sherries.

Valencia

The large Valencia D.O. fans out from the great port city of Valencia and, while its current wine scene is not yet as promising as Utiel-Requena or Alicante, there are some notable exceptions in this hot, humid region that has a long-standing history of producing massive quantities of bulk red wines, some rather uninspiring Meserguera-based white wines; and sweet, mostly pedestrian-quality moscatel mistelas. Valencia’s 47,000 acres of vineyards are divided into four subzonas, Clariano (southwest of the city near the Castilla-La Mancha Almansa DO); Valentino and Alto Turia (both northwest of the city); and Moscatel de Valencia (west of the city and devoted wines made from its namesake grape).

Perhaps the Valencia wine with the greatest reputation is Vicente Gandís Plá’s Fusta Nova Moscatel de Alejandría, a luscious sweet wine, whose historic roots probably go all the way back to the epoch when El Cid chased the Moorish rulers out of the Valencia. Bodegas Murviedro, which moved its main base of operations to the new bodega in Requena, makes a parallel line of Valencia DO wines under the Murviedro and Los Monteros brands. The main difference between Murviedro’s Valencia and Utiel-Requena lines is the use of monastrell in the Valencia DO to go along with bobal, tempranillo and sometimes merlot. Murviedro Reserva, a blend of bobal, monastrell, merlot and cabernet sauvignon that spends a year in French and American oak, is the best of the bodega’s Valencia wines.

Celler del Roure, a new winery in Moixent in the Clairano area, has shown the most promise of any Valencia D.O. red table wine. Pablo Calatayud, the young owner, consulted with Sarah Pérez of Priorat’s Clos Martinet, to produce some of the most stylish red wines ever made in Valencia . Celler del Roure’s Maduresa, their top-of-the-line wine is, a big, extracted , but relatively well-balanced, blend of cabernet sauvignon (30%), merlot (30%), tempranillo (20%), syrah (10%) and mandó (10%), an old Valencia area variety. The early efforts were aged a year in 90% new French oak, which dominated the finish. Les Alcusses (named for a ancient Iberian village nearby) is a dark black wine with sweet, ripe fruit which sees only four months in oak. The Alcusses showed very well with Calatayud’s mother’s delicious casserole of arroz con garbanzos and this writer much preferred it to Calatayud’s more prized Maduresa.

I told Pablo Calatayud that I liked the Les Alcusses better than the Maduresa because it had less oak, he said, “That’s what my father says.”

As in most of my extensive wine travels in Spain, in the Comunitat Valenciana, I found that the so-called lesser wines like Les Alcusses, with less extraction for extraction’s sake and judicious use of new oak (if used at all), were far more enjoyable, both in tastings and with food, than many of the bodegas’ more “serious” wines. Given that it is region not known for high quality white wines, I found some promising young wines, but none of exceptional merit so far However, there were some very good bobal-based rosados and were some very drinkable “little wines,” some made from indigenous grapes–especially monastrell and bobal–and a few modern New World-style red wines that could draw serious attention from new-wave wine aficionados in the American market. I did find a number of exceptional wines, including those wonderful dessert moscatels and Fondillóns.

Once again in Spain an area not known for quality wines has shown great potential. I came away from my trips with the feeling that the Comunitat Valenciana, an area known its Moorish heritage; its oranges, almonds, date palms and paellas; for the cities of Valencia and Alicante and their beaches; the famous Valencian Las Fallas Fiestas; and, now the great cultural City of Arts and Sciences and the America’s Cup could soon become an area known for wines, which are showing a marked improvement with every passing year.

-- Gerry Dawes