By Gerry Dawes

Introductory Notes from Reservaycata.com (Madrid), a wine shop on whose website the article was serialized in two installments:

The article that follows was first published on the net at Thewinenews.com, from the printed version of the October/November 2002 issue of this prestigious American wine magazine. With the consent of the author we offer you what we believe to be one of the most stunning in-depth analysis of current Rioja developments having been written this year. Regardless of having to agree with all his appreciations, this compelling and extensive account will lead you through the exciting new developments occurring in Spain's flagship Appellation for red wines. I was featured in two separate monthly articles (December 2002 and January 2003). Translation into Spanish has been performed by Ernesto de Serdio of Reserva y Cata. Enjoy this superb reading!

Note on the author: Gerry Dawes spent 20 years purveying fine wines to top Manhattan restaurants. Up until he left the wine trade to devote full time to his writing, he worked with such noted authorities as Frederick Wildman, Gerald Asher, Robert Haas, Robert Kacher and many top wineries in California, France and Italy. His avocation, however, has always been the wine, food and culture of Spain, a country in which he has lived and traveled for nearly 30 years. Dawes is considered the leading authority in the United States on Spanish wines. In addition to The Wine News, his articles and photographs have appeared in The New York Times and various national wine publications. He wrote several chapters in The Berlitz Travellers Guide to Spain and is currently writing Homage to Iberia (inspired by James A. Michener's Iberia: Spanish Travels & Reflections).

La Rioja, northern Spain's splendid, red-wine-producing enclave, has been regularly accused of being a sleeping giant by the critics. Many of the loudest voices come from Spain's own cadre of wine writers, some of whom seem to automatically equate the word nuevo with the concept of quality. A few among them have practically made a crusade of denigrating the region's balanced, food-friendly wines, even los buenos clasicos, as Jésus Madrazo, the young, highly regarded general manager of Contino and a descendant of the founding family of CUNE, calls the top traditionalist wines. A couple of these modernista proponents have even conjectured that the old guard's resistance to change is some kind of sinister, post-Franco movement.

Isaac Muga and Jesus Madrazo pouring each other's wine (Contino & Muga) at lunch at Bodegas Muga.

Photo by Gerry Dawes copyright 2004

Because La Rioja is so large and produces so much wine, this old lion may appear to move slowly, but like the mountain cat that it is, once this time-honored region springs to life, it will be hard to hold back. In fact, La Rioja is in a dynamic state of evolution, and many of its classic bodegas are already producing some of the best, modern-style wines in Spain.

The region's metamorphosis was aptly described in a recent issue of Sobremesa, one of Spain's leading epicurean magazines: "The old enological catechisms" are giving way to a new generation of red wines that are "capable of competing with the best wines on the planet." The author highlighted the emergence of a group of Rioja wines that "are escaping their local coordinates and aspiring to place themselves among the world elite."

A visit this spring confirmed the profound changes La Rioja is undergoing. A conference in Logroño entitled "Los Grandes de la Rioja" had drawn a field of international wine writers for a four-day marathon that would encompass a series of catas (tastings), winery visits and winemaker dinners. It soon became apparent, however, that the conference was being largely underwritten by La Communidad de La Rioja (the Rioja provincial government) and not by the official Rioja denominación de origen (DO), which also represents the Basque and Navarrese sections of the DO.

What this meant was that in the tastings (more than 130 wines were poured for evaluation) and visits, there would be no wines from Navarra's Rioja-designated communities, nor from the vital Basque Rioja Alavesa. The latter, which is located on the lower slopes of the Sierra Cantabria mountains north of the Ebro River, is home to many of La Rioja's most important (and some of the most polemic) wineries: Marqués de Riscal, Martínez Bujanda, Faustino Martínez, Remelluri, Contino, Remírez de Ganuza and Artadi among others. Industry insiders said privately that the absence of the Rioja Alavesa DO wines was a result of infighting between the two regional governments.

Fernando Remirez de Ganuza

Gerry Dawes copyright 2004

Putting aside local politics, La Rioja is arguably the greatest red wine region in Spain. And its prowess is still based primarily on the ability of the top centenarian bodegas to produce millions of bottles of high-quality wines at reasonable prices. This core group includes CUNE (Companía Vinícola del Norte de España), La Rioja Alta, Muga, López de Heredia, Marqués de Riscal, Marqués de Murrieta and Bodegas Riojanas. This distinguished group of bodegas makes more bottles of 90-plus-rated wines than the rest of Spain put together.

Francisco Hurtado de Amezaga, Technical Director of Marqués de Riscal, opening old reservas with hot tongs

during the presentation of the plans for the new Frank Gehry-designed hospitality center at the winery.

during the presentation of the plans for the new Frank Gehry-designed hospitality center at the winery.

Gerry Dawes copyright 2004

Marqués de Riscal alone has some two million cases of fine wine aging at the bodega at any one time. By contrast, even in bumper years like 1998 and 1999, the Ribera del Duero produces less than three million cases annually.

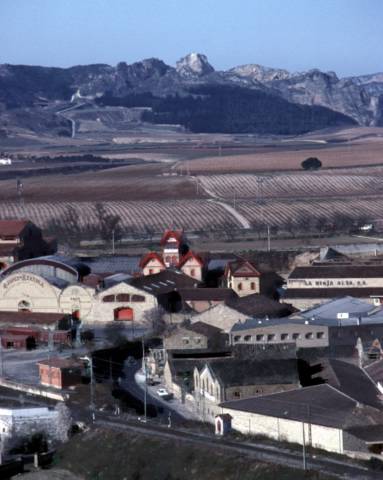

The famous Barrio de la Estación in Haro (Rioja Alta), home to CUNE, López de Heredia, La Rioja Alta,

Bodegas Bilbainas, Muga, Roda and others. Beyond are the vineyards of La Rioja Alta and Rioja Alavesa.

Gerry Dawes copyright 2004

"Some like to say that La Rioja has been asleep, but the reality is that we continue to dominate the market in spite of the rise of other regions, and by a substantial margin," Contino's Madrazo asserts.

By the end of 2000, La Rioja reportedly had more than 130,000 acres in production, more than the Ribera del Duero (35,000 acres), Navarra (37,000 acres) and Priorato (3,500 acres) combined. But while La Rioja produces more red wine than all of those regions put together, not all of it is good. In fact, far too much is lamentably mediocre, a trait La Rioja shares with many other major wine-producing areas in the world. And there are overstocks in some bodegas that are approaching five times their average annual production, a scenario that caused grape prices to plummet in 2000 and 2001, though paradoxically the gross revenues actually increased last year because of higher average prices.

Over the last decade of the 20th century, vineyard acreage expanded by roughly 20 percent as diseased vines and old, underproducing stock were uprooted and replanted in a process that is ongoing. Higher-production clones trained on modern trellis systems and spaced for mechanization are contributing to an increased production estimated at between 50 and 60 percent. (So much for European Union controls to dry up the continent's vast wine lake - ironically, much of the replanting expense is actually being heavily subsidized by the EU.)

In the face of what is being called el crisis de la Rioja, producers of heretofore typical-style Rioja wines, many of which had lackluster reputations, have scrambled to improve the quality of their wines (other overstocked wine regions find themselves in similar predicaments, most notably Beaujolais, where 13 million bottles were recently - and embarrassingly - distilled into vinegar). Spurred by a combination of declining sales in European markets (down 34 percent in Sweden, for example) and the natural desire to compete globally at a higher level, medium- to large-size bodegas and cooperatives are changing their approach to winemaking.

Trasiego (racking) at La Rioja Alta.

Gerry Dawes copyright 2004

Having tasted so many Rioja Alta and Rioja Oriental (Baja) wines, I reasoned that it would be folly to leave without tasting the wines of the Basque Country's Rioja Alavesa. I hastily rearranged my plans to stay another six days. Over the course of my intensive winery visits and tastings in La Rioja, an in-depth picture of the revolutionary changes taking place on several Rioja fronts came into sharp focus. In most of the best traditional houses of Rioja Alta and Rioja Alavesa, 21st-century improvements in vineyard development, vinification facilities and winemaking techniques are dramatically changing the face of winemaking here. Even in La Rioja Baja/Oriental, traditionally the backwater of the region, quality is on the rise.

Isios winery near Laguardia

Gerry Dawes copyright 2004

Among the most important developments is the dramatically intensified focus on the vineyard, and thus grape quality, especially in the emerging, small-producer bodegas of La Rioja Alavesa.

Indeed, the current breeze of change prevailing in La Rioja is blowing from the vineyards. During the first 25 years I traveled there, I was almost never invited to tour the vineyards. Rather, my encounters largely took place in the cellars.

Tinos (wooden vats), La Rioja Alta

Gerry Dawes copyright 2004

(The same was generally true of my visits to Champagne and even Burgundy during that period.) In the past five years, however, I've seen more Rioja vineyards in the company of winegrowers than in my first quarter-century of combined visits.

This new-found interest in terroir is reflected in the number of site-specific wineries that have sprung up across the region over the past decade. Established to make luxury cuvées from pagos, or single vineyard and estate sites, these wineries are moving toward a Burgundian philosophy that is sure to lend additional excitement to their winemaking approach.

Andrés Proensa, the moderator of the Los Grandes de La Rioja conference and one Spain's top wine writers, approves of the change in philosophy. "La Rioja is living in a very interesting moment and undergoing a notable change in attitude," he says. "Not long ago, the thrust of the winemaking was in the cellars, and the vineyards were considered to be secondary - almost a necessary evil. Now Rioja producers are turning an eye toward the vineyards and this is changing the wines of the region for the better. Not just the modern and expensive wines, but the shift is also affecting the quality of wines priced at moderate levels."

The manner in which the conference tastings were presented illustrated the changes under way in La Rioja. The flights were arranged into seven categories: ecológicos (organic), estilo tradicional (traditional style), blancos con madera (whites with oak aging), renovados (new style), tintos cosecha 2001 (reds from the 2001 harvest), vanguardia (ultramodern) and grandes clásicos (great classics).

Among the renovados were the alta expresión wines, a style that has been the subject of an often-heated debate among wine professionals and aficionados. The term was coined to categorize the usually big, powerful, dark, quite ripe wines, often loaded with French oak, that carry hefty price tags in the $50 to $100-plus range (see Alta Expresión Vino, April/May 2001). Had the Basque wines also been included, there would undoubtedly have been more categories, such as cosechero-viticultor (grower-vintner) and vinos de pago (single-vineyard wines).

Very much at odds with the alta expresión approach to winemaking is Manuel Camblor, a passionate and knowledgeable collector who lives in New York City (and who now lives in La Republica Dominicana). A creative home and furniture design consultant, he developed his palate for Rioja gran reservas at his late grandfather's side in the Dominican Republic. At first, Camblor was excited about the new wave of Spanish wines that began to emerge in the mid-1990s. He had the means to buy them and did.

Over the intervening years, as he pulled one expensive bottle after another from his cellar, he found none lived up to its billing. Disillusioned, he recently posted his concerns on El Mundo's Web site: "When wines begin to have aspirations to greatness, encouraged by certain critics who speak of their potential and put them in the same league with wines which over their history have earned a reputation, my skepticism was awakened."

La Rioja Alta, S.A.

Gerry Dawes copyright 2004

Several of the revered, proven producers to which Camblor alluded recently founded the Agrupación de Bodegas Centenarias (Centenarian Bodegas Group) to promote and defend their image. But for some time, traditional Rioja houses such as CUNE, Marqués de Riscal, La Rioja Alta and Marqués de Murrieta have been steadily upgrading their equipment. Most of them now have state-of-the-art, computer-controlled, vinification facilities, so don't let anyone tell you that these classic bodegas - no matter how picturesque their facades and museum-esque buildings may be - are mired in the past. It just isn't so.

With the exception of the great virtual working wine museum, R. López de Heredia, which has steadfastly remained true to its traditions, many of the big, classic bodegas boast facilities on par with model California wineries. In particular, CUNE has had a technically spectacular, gravity-force operation for a decade; La Rioja Alta has built a large vinification site across the Ebro River just a couple of miles away from their early 20th-century bodega; and the ultramodern vinification plant at Marqués de Riscal is absolutely stunning.

The epic of the ongoing evolution at most of the great, classical Rioja bodegas is a story in itself, because in no other region in Spain are so many high-quality, traditional-style wines being made in tandem with so many exciting New Age wines. Indeed, over the past several years, almost all of the top Rioja bodegas have developed modern-profile wines meant to compete not only with Rioja's alta expresión wines, but also the tinto fino (tempranillo) mono-varietal, merlot-esque wines of the Ribera del Duero, the lush, high-octane wines of Priorato and a pandemic sprouting of powerful, French oak-basted New World-wannabes from all around Spain.

The big difference is that most of the contemporary wines from the best old-line, Atlantic-climate, Rioja bodegas are well-balanced and eminently drinkable. In fact, remarkably few have overstepped the bounds of good taste to enter the international wine sweepstakes. Wines such as CUNE's exceptional Real de Asua, Marqués de Riscal's cabernet sauvignon-laced Barón de Chirel, Marqués de Murrieta's Dalmau; Bodegas Muga's Super-Rioja, Torremuga; Martínez Bujanda's estate-grown Valpiedra; and Palacios Remondo's Herencia Remondo Propiedad have shown they can compete in the high-stakes, vino moderno game themselves.

The historic buildings at CUNE, Compañía Vínicola del Norte de España.

Gerry Dawes copyright 2004

"With more than a century of making fine wines to our credit, we know a thing or two about making great wines in both classic and modern styles," observes Madrazo, who makes the increasingly elegant wines of the Contino estate.

A number of fledgling wineries - some representing substantial investments, others on a relative shoestring budget - have surfaced in La Rioja over the past 20 years. Since 1985, more than 50 bodegas have opened, a figure that doesn't even include the very small operations among the 420-odd registered bodegas that don't show up on Rioja DOs radar screen. The most highly regarded among this group of relative newcomers are Roda, Marqués de Vargas, Telmo Rodríguez, Remírez de Ganuza, Artadi, Finca Allende, Campillo (owned by Faustino), Ondarre (owned by Olarra), Barón de Ley, Marqués de Griñon, Barón de Oña (now owned by La Rioja Alta), Señorío de San Vicente, Abel Mendoza, Miguel Merino, Luberri-Monje Amestoi and Viña Villabuena. Most of these bodegas register high on the New Age vino del autor scoreboard.

Agustin Santolaya pouring some of the 21 wines at a midnight tasting he organized for me at Roda in April 2003.

Gerry Dawes copyright 2003.

In response to this rising tide, the Rioja Baja region (which is now trying to reposition itself as La Rioja Oriental), is trying to establish its own regional identity. Historically, this southeastern section of Rioja has been the supplier of recourse for more robust, higher alcohol, Mediterranean-continental climate, garnacha-based wines used to beef up the crianza (and sometimes reserva wines) of the bodegas of La Rioja Alta in leaner years. Now wineries such as Palacios Remondo in Alfaro, under the guidance of Álvaro Palacios, are turning up the heat.

Palacios, who has become an international wine star because of his L'Ermita single-vineyard wine from Priorato, hopes to show that outstanding wines can be made in this heretofore little-appreciated area of La Rioja. A major advocate of the single-vineyard approach to producing superb wines (he has several spectacular vineyards in Priorato, La Rioja and the emerging Bierzo area), Palacios says, that "What we want to establish in our eastern zone is precisely the geo-climatic and varietal differences between grapes grown in the different areas of La Rioja, showing with absolutely dignified wines how distinctive the flavors in each region can be."

Palacios is convinced that "If La Rioja does not begin to offer wines that show the charm of its provenance and encourage its zonal distinctions, local microclimates and specific vineyard sites, it will continue to be a great wine region that produces a high volume of good quality wines at medium-to-low prices for large numbers of consumers, but it will never produce wines of exceptional quality."

The problem, Palacios says, "is the lack of [Rioja] wines that have truly elite status. A wine region has to have certain designated areas or single vineyards to create great works of viticultural art. In my opinion, La Rioja still has not yet done that."

It is hoped that Palacios's new Herencia Remondo Propiedad (a blend of 40 percent garnacha, 35 percent tempranillo, 15 percent mazuelo and 10 percent graciano) is indicative of what's in store here. Harvested from the family's 250-acre La Montesa vineyard situated 1,800 feet above sea level on the slopes of the Sierra de Yerga, the 1999, 2000 and the exceptional 2001 vintage of Propiedad may be the best wines ever produced in La Rioja Baja/Oriental.

Suddenly, in a region where, historically, most of the emphasis has been on elevating the juice in the winery into something quite palatable (and often, very, very good), everyone is beginning to focus on grape quality by taking control of their own grape sources and paying more attention to terroir.

In La Rioja Alta, Finca Valpiedra, Finca Allende and Señorío de San Vicente are notable for their distinctive sites, but the movement toward single- vineyard plots is strongest in La Rioja Alavesa, where a number of small producers with very old vines show the promise of the region. Such Alavesa producers as Contino, Remelluri, Remírez de Ganuza and Artadi are proving they can attract international attention with wines made from single-vineyard sites or a series of separate single vineyards. Producers such as Valdelana, Luberri Monje Amestoi and Ostatu draw from exceptional sites as well.

There are also a number of cosecheros-viticultores (grower-producers) in La Rioja Alavesa who have relatively small, single-vineyard pagos that have been in their families for generations; it is not uncommon to find vineyards here that are 50 to 80 years old. These producers are reminiscent of small Burgundy winegrowers, and some have the potential to craft extraordinary wines from these sites. The problem at this juncture is that many of them, with the help of Basque government subsidies, have only recently begun to attempt making serious, age-worthy wines. Traditionally, most made deeply fruity, rich, carbonic maceration cosechero vinos del año, a Beaujolais-style wine that was sold cheap and meant to be drunk before the next harvest. The wines were often delicious, but certainly not intended to sit on retail shelves for very long.

Many of these producers simply don't have the depth of experience necessary to make world-class wines from these quintessential grapes. Some have brought in consultants to advise them. Doroteo Sáenz de Samniego of Ostatu enlisted Bordeaux's Hubert de Boüard de Laforest, owner-winemaker of St.-Emilion's Château L'Angelus, to help him select three of his best parcels for his top-of-the-line Gloria de Ostatu, and he now uses 65 percent French oak (five types), because "Americans like French oak better," he says. Others, such as Florentino Martínez whose pampered vineyards at Luberri-Monje Amestoi en Elciego yield some of the best juice in La Rioja Alavesa, have followed the modern trend toward over-oaking their otherwise excellent wine (although Martínez says he is seriously considering lowering the percentage of new oak he uses). Some, such as Abel Mendoza in neighboring Rioja Alta and Señorío de San Vicente, are making new-wave wines that show great promise, but have been hyped out of proportion to their actual quality.

The Rioja Alavesa can be a confusing place to outsiders because its wineries run the gamut from the huge, internationally known Marqués de Riscal to the small, cosechero family home wineries such as Ostatu and Luberri Monje Amestoi. In between are the modern, high-production wineries such as Faustino Martínez, Martínez Bujanda and Campillo, and a string of good, medium-size, often family-owned wineries, such as Luis Cañas, Valserrano, Larchago and Valdelana. Then there are the single- vineyard estates such as Remelluri and the first-rate Contino. Even the main cooperative, the Unión de Cosecheros de Labastida (Grower's Union of Labastida), is one of the best in Spain. But the Basque region, with its separate and often peculiar politics, has incredible potential and will undoubtedly be the micromodel for what much of the rest of the Rioja will become in time.

"Producers in La Rioja are opening their minds to all kinds of influences - not all good, regretfully," Andrés Proensa noted at the conference. "[But] there is a new generation of winemakers, more or less young people, who are working with their heads in the cellars and their feet in the vineyards, studying soils, microclimates, grape varieties, production, vineyard treatments, grape maturation, and later crafting a style of wine that complements the terroir by choosing with great care how they make the wines, choose the types of oak, toast the barrels, the aging regimen and all the rest."

Contino's Madrazo is counted among this breed of enlightened winemaker. His carefully crafted wines are becoming more stylish and balanced with each vintage. The brother team of Álvaro and Rafael Palacios is adhering to a similar formula at Palacio Remondo, as are the young Muga cousins, who are responsible for Torre Muga. Not to be overlooked are Finca Allende's gregarious Miguel Angel de Gregorio, and Juan Jésus Valdelana of Bodegas Valdelana's Jésus de Valdelana, whose young wine is a work of art. At the 150-year-old Marqués de Murrieta, Vicente Dalmau Cebrián-Sagárriga has assembled a winemaking team whose average age is 29. He took over a few years ago after his father's sudden death and is guiding the bodega into the 21st century. His eponymous Dalmau is a thoroughly modern vino del autor wine, but it preserves the best of Murrieta's classic style.

María José López de Heredia in the 'cementerio' of her family's winery.

Gerry Dawes copyright 2004

Even the four young siblings (two women, two men) at R. López de Heredia are making their presence felt at that venerable institution. In a gesture that likely was unprecedented at this 125-year-old bodega, members of the Los Grandes de La Rioja group were allowed to taste a one-year-old wine, the 2000 vintage of Viña Tondonia. It may sound like a small thing to those accustomed to New World winemaking, but this simple offering spoke volumes about these enlightened young lions. Their generation will undoubtedly leave an indelible imprint on the storied wines of La Rioja. For now, they've already sent this big, sleeping cat a wake-up call that is resonating across Spain.

This article first appeared in The Wine News, Oct/Nov 2002